Should Congress Be Fired?

Why America Keeps Flipping the House — and Nothing Gets Fixed

In American politics, there is one ritual more reliable than any campaign promise:

Every two years, voters punish Congress.

And the midterm season isn’t coming — it’s already here

Just like March Madness, the bracket starts early: primary season tips off in March — Arkansas, North Carolina, and Texas vote March 3, Mississippi follows March 10, and Illinois on March 17. The midterm clock is already ticking.

Sometimes that punishment flips control of the House. Sometimes it doesn’t. But almost always, the party governing the House loses ground—seats, stability, leverage, or all three.

And the reasons voters give are rarely procedural.

Most Americans don’t track markups.

They don’t know who chairs Rules.

They don’t score legislative output.

They experience Congress as a feeling: chaos, gridlock, brinkmanship, noise.

Pundits love to say midterms are a referendum on the president. If that were the whole story, it would mean nearly every modern president “failed” by year two—because the president’s party almost always gets hit in the House.

That’s not analysis. That’s ritual.

The better explanation is structural.

In a locked-in electorate, midterms aren’t decided by the base. They’re decided by a shrinking sliver of persuadable voters who aren’t voting for a governing vision—they’re voting against a mood. They flip the House less as a reward for the other side and more as a release valve for a system that feels overheated.

So the real question isn’t, “Why does the House sometimes flip?”

It’s deeper—and more uncomfortable:

Why has Congress become the easiest place for voters to register dissatisfaction, even when it makes governing harder?

To answer that, we have to stop starting in Washington—and start where elections are actually decided: with the small slice of voters who are still movable, and who punish dysfunction faster than they reward results.

Prologue: The Voters Who Decide Everything

Modern elections are not decided by “the American people” in the abstract.

They’re decided by a very small slice.

At Zoose, we track this relentlessly, and the math has barely budged in years. Roughly nine out of ten voters are already spoken for. They are locked into one side or the other, immune to persuasion, and largely unreachable.

What’s left — the sliver that actually decides midterms — is small and fragile.

About five to seven percent of voters are truly persuadable: late-breaking, low-engagement, allergic to chaos, and deeply distrustful of both party brands. This group is growing younger, more independent, and less patient — especially among Gen Z and Millennials, where “Independent” identification is now at record highs.

That changes everything.

Congress is not being judged by 100 percent of voters.

It’s being judged by the five percent who haven’t tuned out — and who react more to feelings than platforms.

Ninety percent of voters already know who they support or oppose.

And within that remaining slice, only a fraction is truly movable — and they’re the ones who decide who gets punished.

They don’t reward ideology.

They punish dysfunction.

This is why polarization doesn’t just cause gridlock.

It guarantees midterm backlash.

The Rule: The House Almost Always Gets Fired

There is one rule in modern American politics that almost never breaks:

The party in the White House almost always loses the House at the midterms.

It doesn’t matter if the economy is growing.

It doesn’t matter if bills passed.

It doesn’t matter if the president is popular.

The House gets punished anyway.

Since World War II, there are only two midterms where the president’s party actually gained House seats: 1998 and 2002.

And those exceptions aren’t trivia question. They explain everything that followed.

1998: Clinton and the Impeachment Backlash

While the House didn’t flip in 1998, the majority still got punished.

Republicans overreached on impeachment, and the electorate responded by giving Democrats five additional House seats — one of the couple times in modern history the president’s party gained ground in a midterm.

This wasn’t ideological alignment.

It was institutional judgment.

Voters looked at Congress and said: you’re the problem.

And it’s worth remembering: the impeachment fight didn’t come out of nowhere. The modern era of partisan warfare was already underway after 1994 — Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America,” the nationalization of House races, and the rise of a new media ecosystem (Rush Limbaugh and the talk-radio era) that rewarded confrontation over compromise.

One quiet inflection point came even earlier, in the Reagan era: in 1987 the FCC repealed the Fairness Doctrine, accelerating the shift from a broadcast model that nudged balance toward a market model that rewarded audience capture. It didn’t create polarization. It commercialized the business model that profits from it. By the time Congress reached impeachment, the incentives were already set.

1998 wasn’t the beginning of polarization — it was an early stress test of what happens when Congress turns conflict into the governing brand.

2002: Post-9/11 Unity

The only other exception came four years later.

In 2002, Republicans gained House seats under George W. Bush — the only modern GOP president to do so in a midterm.

Why?

Because the country wasn’t polarized.

It was unified.

After 9/11, Americans weren’t sorting by ideology. They were sorting by survival. Congress benefited from a level of national alignment that simply does not exist anymore — and likely never will again.

Those two moments — 1998 and post-9/11 — are the last times the House escaped punishment.

Every cycle since?

The blade has fallen.

When Polarization Took Over

From the mid-2000s onward, something fundamental changed.

The Iraq War fractured trust.

Cable news hardened identities.

Primaries became more dangerous than general elections.

Social media rewarded conflict over competence.

By the time we reached the Paul Ryan era, the House was no longer built to govern.

The Paul Ryan Congress (2015–2018)

Ryan inherited what should have been a dream scenario: an ideologically aligned Republican majority and, briefly, unified government.

Instead, he presided over an institution defined by brinkmanship — budget standoffs, debt-ceiling threats, symbolic votes with no legislative endpoint, and intraparty revolts that made governing feel optional.

Even when Republicans controlled everything in 2017–2018, the House could not project competence.

Voters noticed.

Republicans lost 40 House seats in 2018.

Ryan retired before the election — a quiet acknowledgment that the institution itself had become unmanageable.

Voters didn’t fire Trump in 2018.

They fired Congress.

Again.

The Pelosi Congress: Productive on Paper, Partisan by Design

After the Ryan years, the House didn’t calm down.

It institutionalized its conflict.

That was the Nancy Pelosi Congress: disciplined, legislatively active — and culturally radioactive.

This was not a House paralyzed by chaos.

It was, in many ways, the opposite.

Pelosi presided over a chamber that could move legislation when it chose to — and did. Leadership held. Committees functioned. The Speaker’s gavel actually meant something. But the price of that competence was a governing strategy that leaned hard into partisanship.

On substance, the Pelosi House delivered real laws — often at scale:

The American Rescue Plan — a sweeping COVID relief package passed entirely along party lines, with zero Republican support, using reconciliation to bypass negotiation

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — a rare bipartisan achievement, but one Pelosi deliberately paired with partisan leverage to keep her caucus unified

CHIPS and Science Act — bipartisan at first, then increasingly polarized as it became folded into national political combat

The Inflation Reduction Act — climate, healthcare, and tax policy rolled into a single, fully partisan vehicle with no GOP votes

Measured purely by output, this was one of the most legislatively active Houses in decades.

But how those bills passed mattered as much as that they passed.

The Pelosi Congress proved that the House could still govern — as long as it governed by choosing winners and losers in advance.

And culturally, that choice defined everything voters saw.

This was the House that:

Made investigation and oversight the organizing principle of governance

Impeached Donald Trump twice, placing Congress at the center of national political warfare

Turned floor votes into symbols of alignment rather than persuasion

Normalized governing through narrow margins and procedural muscle

Even when legislation moved, the signal voters received wasn’t stability.

It was escalation.

For the 90% of voters already locked into partisan camps, that escalation felt either righteous or enraging — but irrelevant. Their votes were already spoken for.

For the remaining persuadable slice, it felt like Washington was consumed by itself.

The Pelosi Congress proves a critical Zoose insight:

Legislative productivity does not protect a Congress if voters experience it as culturally ungovernable.

Democrats held the House in 2020. They passed major laws. They exercised power.

And yet the cumulative effect of inflation, pandemic fatigue, and a Congress defined more by confrontation than coalition produced the same outcome history predicts.

In 2022, voters flipped the House.

Not because nothing passed —

but because everything felt partisan.

Pelosi represents the high-discipline version of polarization:

Strong leadership

Real legislation

And a political cost that still arrived on schedule

Which brings us to the present — a House that is less productive, more fragile, and even more exposed to the same voter instincts.

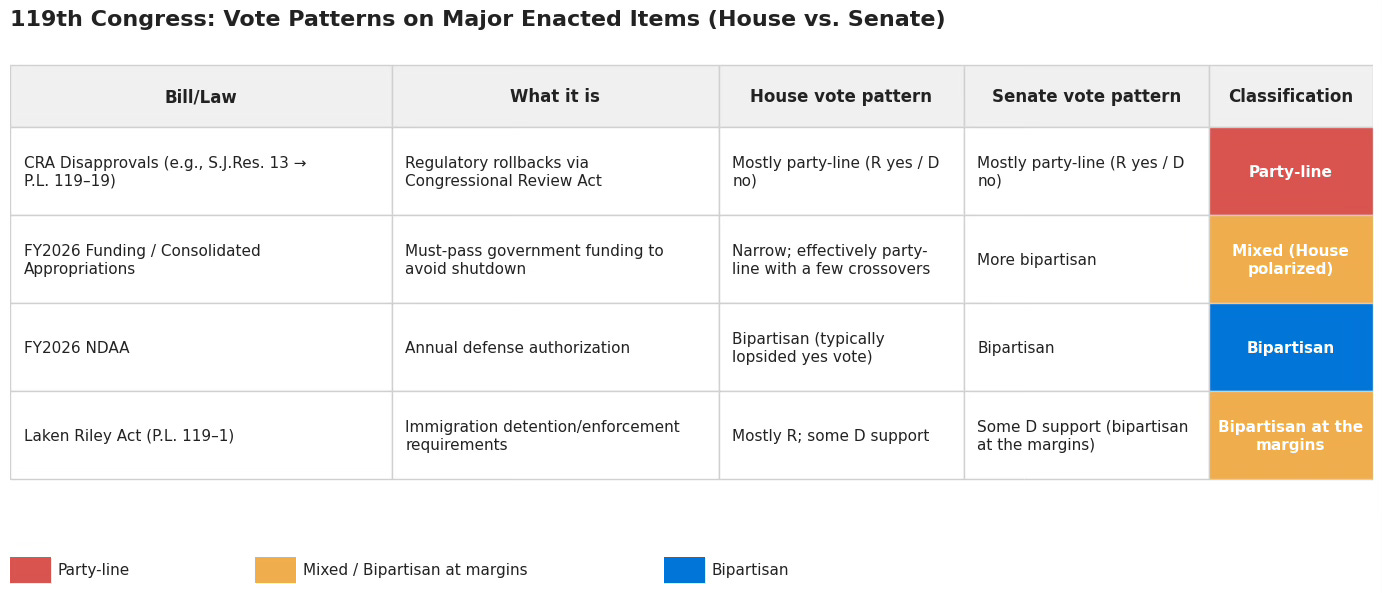

The 119th Congress: Evidence, Not Theory

If you define “significant” as laws that actually change government operations — not press releases — the 119th Congress has legislated in just a few narrow lanes.

Defense.

Funding.

A single high-salience immigration bill.

And regulatory rollbacks through the Congressional Review Act.

Everything else has stalled.

And the way those bills passed matters as much as what passed — because it shows what Speaker Mike Johnson is really managing.

In this House, Johnson isn’t leading a majority that governs. He’s arbitrating a coalition that vetoes: a handful of members can threaten the Speaker’s job, block a rule, or blow up the calendar. That means most “governing” only happens under deadline pressure — when the alternative is shutdown, collapse, or public blame.

So the record isn’t just narrow. It’s conditional — the product of deadlines, brinkmanship, and coalition management, not routine governance.

Defense moved because failure wasn’t an option.

Funding passed narrowly in the House and comfortably in the Senate.

Immigration drew bipartisan support only at the margins.

CRA votes were almost perfectly party-line.

Another example of the House’s current priorities came this past Wednesday, when it passed the SAVE Act (Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act) — a federal voter-eligibility bill requiring proof of U.S. citizenship to register for federal elections (and tied to tighter ID standards).

The vote was closely divided and largely along party lines, and the measure now awaits action in the Senate. It isn’t law — but it shows something important about this House: it can still move high-salience, politically charged bills when the incentive is partisan clarity, even if bipartisan consensus is absent.

The pattern is unmistakable.

The House governs only when it has no choice.

Everything else becomes theater.

Polarization doesn’t paralyze Washington evenly.

It concentrates dysfunction where voters can see it most clearly.

Why the Senate Survives — and the House Doesn’t

This isn’t because senators are nobler.

It’s structural.

Senators have six-year terms.

House members live in permanent campaign mode.

Tiny factions can veto leadership.

Speakers manage factions, not parties.

When ten members can topple a Speaker, governance becomes optional — and chaos becomes leverage.

The Senate absorbs polarization.

The House amplifies it.

How Voters Experience This

Most voters don’t read bills or track process.

They experience Congress the way they experience everything now: through moments.

Shutdown countdowns. Speaker drama. Viral clips. Cable chyrons.

A steady drip of conflict with no visible payoff.

So the persuadable middle asks one question:

Does this place work — or is it just fighting?

When it feels like “just fighting,” the verdict comes fast.

They don’t fire Congress ideologically.

They fire it emotionally — as a release valve.

That’s it.

The Uncomfortable Conclusion — Why Congress Keeps Getting Fired

The persuadable middle isn’t voting for a governing vision.

They’re voting against a feeling.

They are not grading Congress on legislative output or bipartisan ratios. They are not asking whether seven of twelve priority bills passed.

They are asking something much simpler:

Does this feel chaotic, exhausting, and disconnected from my life?

When the answer feels like “yes,” the response is automatic.

They punish.

Switching control of the House every two years isn’t a plan to govern better. It’s a release valve.

When voters feel overwhelmed, unheard, priced out, and culturally trapped between extremes, they reach for the only lever that still feels responsive. Flipping the House is less about belief — and more about relief.

That instinct isn’t irrational.

It’s adaptive.

Why Midterm Switching Makes Sense to Voters

From the voter’s perspective, this behavior is logical.

They’re operating under three constraints:

They don’t trust party brands

They have little influence over primaries

They can’t see a clear link between legislation and daily life

So they default to a blunt accountability rule:

The House absorbs that anger because it is the most visible, the most chaotic, and the most permanently in campaign mode.

Switching control isn’t indecision.

It’s the only accountability mechanism that still feels real.

Balance Over Outcomes

Here’s what most analysts miss.

Most persuadable voters do not want one side to fully win.

They want friction.

They want limits.

They want brakes.

They believe that divided government prevents excess. So when one party controls the White House, the House, and the narrative, the instinct is not endorsement.

It’s correction.

They fear domination more than dysfunction.

The Time Horizon Problem

Governing is not a two-year project.

Real outcomes require:

multi-year implementation

policy lag

economic absorption time

But voters are asked to judge performance every 24 months.

By the time results begin to appear, the majority has already changed, continuity has been broken, and blame has shifted.

That’s not voter ignorance.

It’s a time-horizon mismatch baked into the system.

Why This Is Worse Now

This dynamic accelerates when:

~90% of voters are locked into partisan camps

the persuadable middle shrinks to ~5%

media rewards outrage over patience

social trust collapses

In earlier eras, voters believed: “If we give them time, they’ll figure it out.”

Now the belief is: “If we don’t punish them quickly, they’ll never listen.”

That shift explains why the House flips more often — and more violently — than any other institution.

The Exception That Matters: Trump Defying The Odds

All of this makes Congress look doomed — and structurally, it probably is.

If midterms were truly a referendum on the president, the historical verdict would be absurd. By the strictest measure — gaining House seats while his party already held power — only one modern president has ever “passed”: George W. Bush in 2002, under the extraordinary conditions of post-9/11 national unity.

The only other comparable moments came under equally exceptional circumstances: Franklin Roosevelt in 1934, amid the New Deal and the Great Depression, and Bill Clinton in 1998, when voters reacted against impeachment by adding Democratic seats without changing control.

That’s not a performance scorecard.

It’s a reminder that midterms are driven by mood, not management.

But American politics has a habit of breaking its own rules at the edges.

And the clearest recent example is Donald Trump.

By every traditional measure, his political career should have ended years ago:

impeached twice

criminally convicted

consistently underwater in approval

relentlessly polarizing

And yet, he won again.

Not because voters suddenly embraced chaos — but because they judged the alternative as less credible, less grounded, and less connected to their daily lives.

That matters for Republicans.

Because it reminds us that midterms aren’t decided by history alone.

They’re decided by contrast.

Right now:

Democrats have one of the weakest party brands in modern polling history

The leftward drift of the Democratic base is accelerating

Persuadable voters aren’t asking for perfection — they’re asking for relief

That doesn’t mean Republicans are immune from the House-flipping curse.

It means the curse can be softened, sharpened — or, under the right conditions, temporarily defied.

The House usually flips.

But margins still matter.

And margins determine:

how governable the next Congress is

whether the Senate remains a firewall

whether power feels checked or runaway

History punishes chaos.

But it also punishes imbalance.

When voters believe one side has gone too far, the ritual pauses.

Not forever.

Just long enough to change the map.

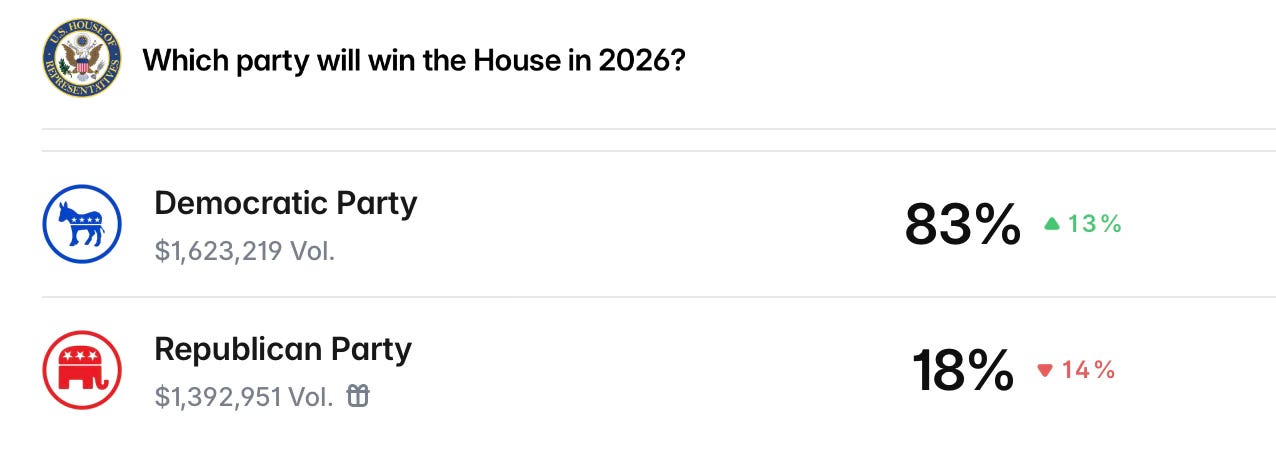

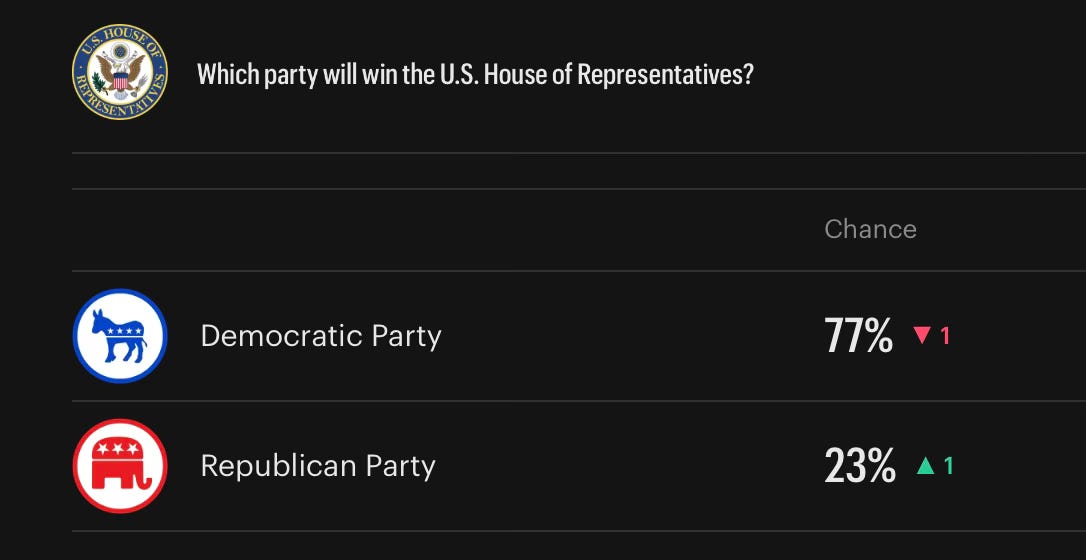

🔮Polymarket— The Crypto Prediction Market

Polymarket is a decentralized, blockchain-based prediction market where users trade on the outcome of future events — from elections to geopolitics to pop culture. It was once banned from the U.S. because it lacked regulatory approval, but it has been moving toward proper licensing and U.S. access through regulatory channels.

📊 Kalshi— The Regulated Prediction Exchange

Kalshi is the first federally regulated prediction market platform in the U.S., registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). It offers event contracts — effectively binary outcome “derivatives” — to U.S. traders.

📺 This Week on Newsmax

This week on Finnerty, I joined E.D. Hill to unpack Zoose’s latest Senate outlook: why Mary Peltola is competitive against Dan Sullivan in Alaska despite a red presidential baseline, what makes James Talarico a different kind of Democrat in Texas, whether Paxton vs. Cornyn changes the odds of a Democratic upset, and why Maine — Collins vs. Mills or Platner — could decide whether Republicans hold their New England firewall.

NJ-11 Update: And the Winner Is… the Progressive Wing

Analilia Mejia is the Democratic nominee in New Jersey’s 11th Special Election.

And the way she won matters as much as the fact that she did.

Mejia didn’t win as a placeholder.

She won as a statement.

A progressive organizer — not a machine-backed candidate — defeated former Congressman Tom Malinowski and a crowded Democratic field, finishing first in an 11-candidate primary with 29.3% of the vote, edging Malinowski’s 27.6%.

Malinowski conceded days later, clearing the runway for a general election matchup against Republican Joe Hathaway, the mayor of Randolph Township, on April 16, to fill the remainder of Mikie Sherrill’s term.

This wasn’t a fluke.

It was a successful ground war by a progressive operative who recognized an opportunity.

Organizer, Not Apparatus

Mejia ran explicitly against the idea of inherited political machinery.

“I am not the candidate with the political machine,” she said in a digital ad.

“I am an organizer.”

And she ran like one.

Backed by Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Elizabeth Warren, Pramila Jayapal, Ro Khanna, and progressive labor groups, Mejia fused national energy with local field work — a combination that has become increasingly potent in Democratic primaries.

While Malinowski was being targeted by millions in outside spending — particularly from the United Democracy Project, aligned with AIPAC — Mejia consolidated progressive voters who were less interested in Washington positioning and more interested in movement politics.

She didn’t just survive the negative air war.

She slipped through it.

And that, too, is part of the story.

Why This Win Is Bigger Than NJ-11

If this feels familiar, it should.

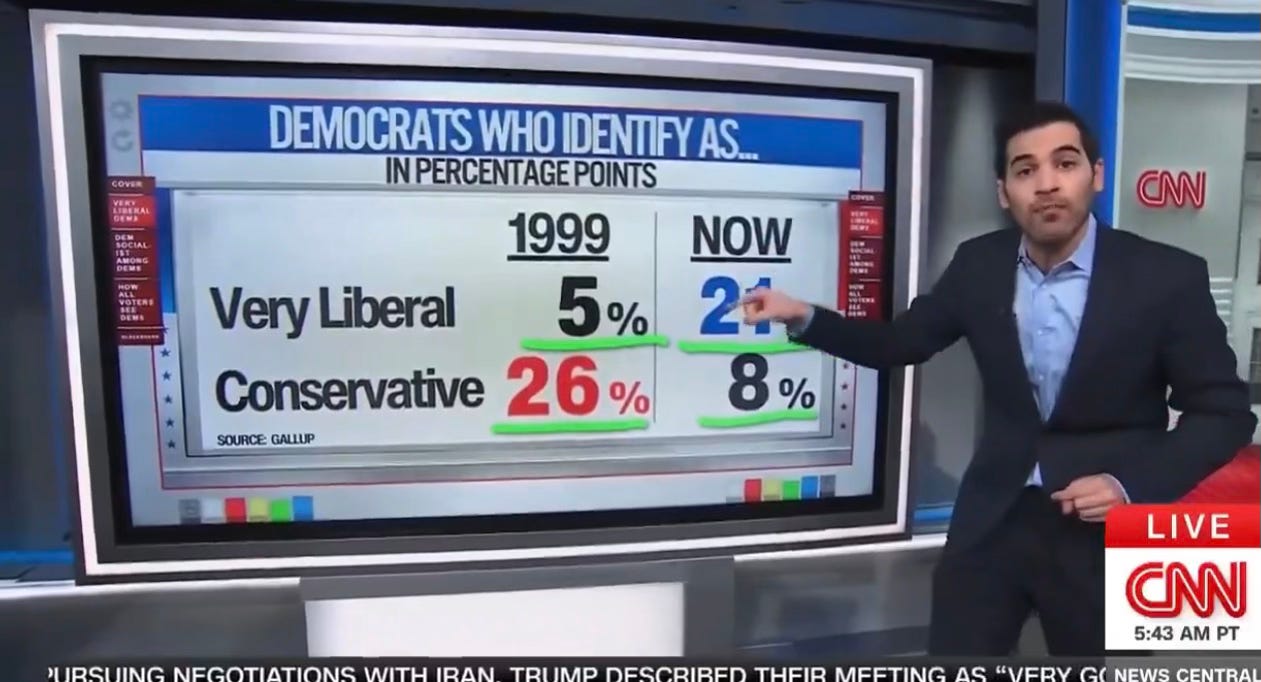

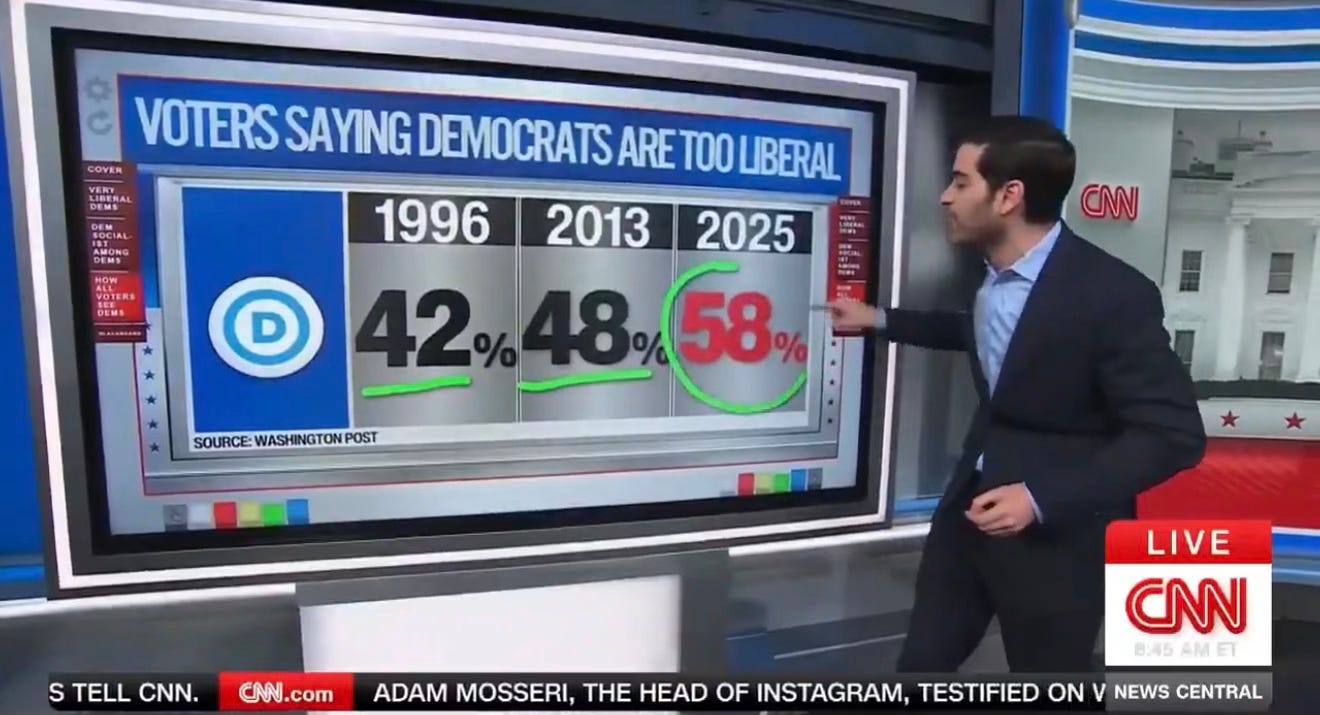

CNN’s Harry Enten put the Mejia win in national context this week — and the data backs it up.

What used to be a fringe inside the Democratic Party is now a pillar:

In 1999, 26% of Democrats identified as conservative

Just 5% identified as very liberal

Today:

21% of Democrats identify as very liberal

Only 8% identify as conservative

Nearly 60% identify as somewhat or very liberal

And among Democrats under 35?

42% identify as Democratic socialists

This is not a coastal anomaly.

It’s a structural shift.

Mejia didn’t invent this trend.

She rode it.

The Tension Democrats Can’t Avoid

While the Democratic base has moved left, the country has not moved with it.

According to the same data Enten highlighted:

58% of all voters now say the Democratic Party is too liberal

That gap — between an energized progressive base and a skeptical general electorate — is where the next phase of this race will be decided.

Mejia now heads into an April 16 special election in a district Mikie Sherrill carried by 15 points just two years ago. On paper, Democrats should hold it.

But the meaning of this race now extends beyond the district:

Can a movement-powered progressive translate primary energy into general-election comfort?

Can Democrats harness activist momentum without triggering persuadable backlash?

And how often will voters see wins like this before they stop calling them surprises?

Zoose Takeaway

Analilia Mejia’s victory isn’t about one district.

It’s about who is winning Democratic primaries — and why.

Progressives are no longer a faction that occasionally breaks through.

They are an organized, funded, culturally confident wing of the party.

That strength wins primaries.

Whether it wins governing majorities is the unresolved question — in New Jersey, and nationally.

Next up: April 16.

This time, the winner won’t just speak to Democrats.

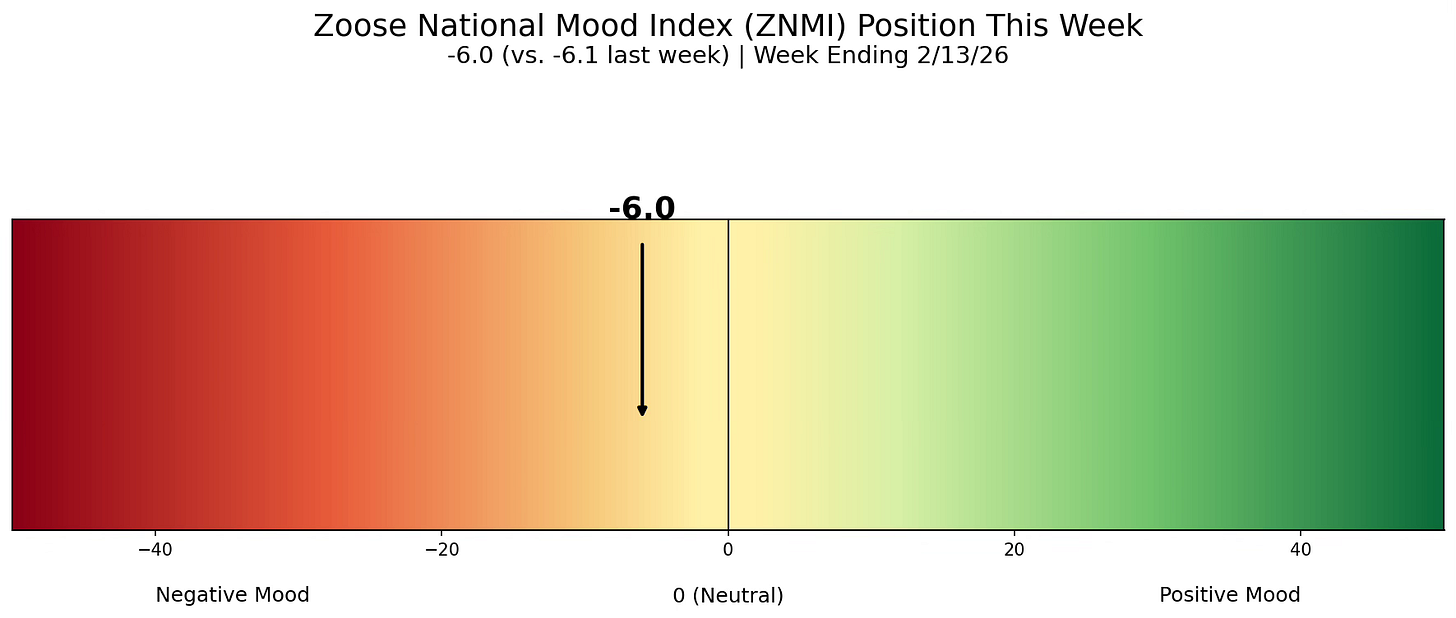

📊 Zoose National Mood Indicator—Slight Improvement

The national mood improved marginally this week, driven by a rebound in presidential approval. However, that gain was largely offset by worsening right track / wrong track sentiment and a slightly more Democratic-leaning generic ballot. Overall, the mood remains moderately negative and fragile rather than meaningfully improving.

📡 Weekly Mood Signals — Week Ending 2/13/26

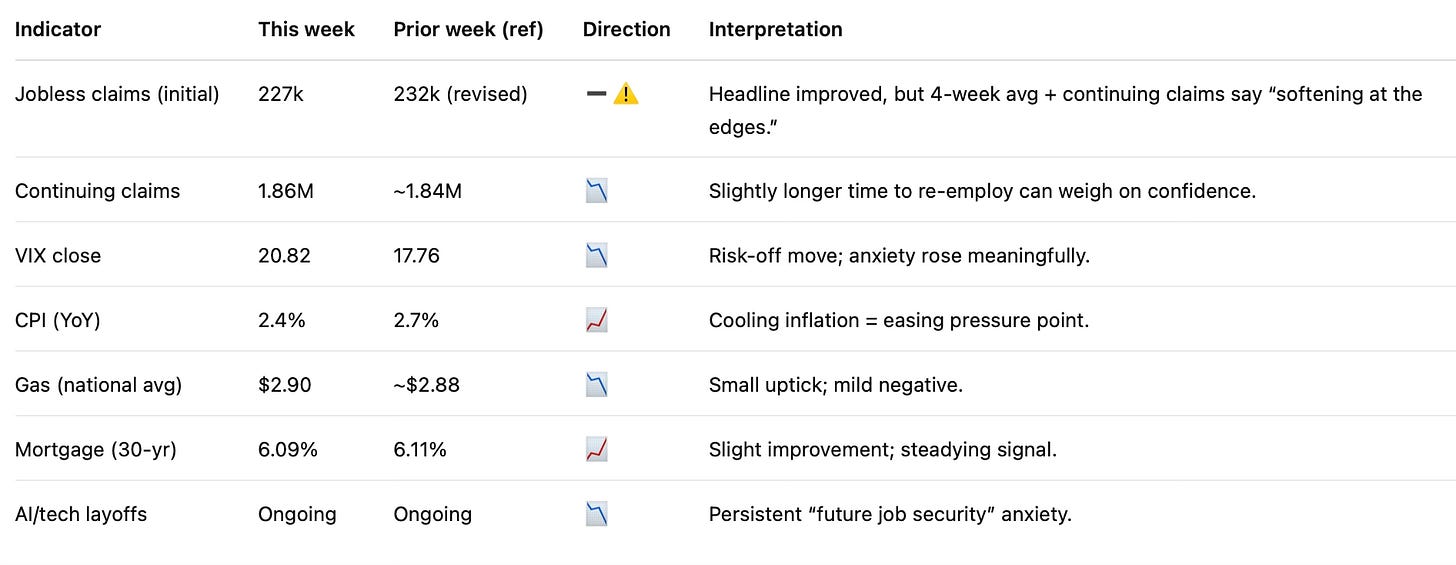

⚠️📉 Jobless Claims — Holding Pattern, Slight Softening

Initial claims fell to 227,000 (down 5,000 WoW), but the 4-week average rose to 219,500 and continuing claims ticked up to ~1.86M — a sign the labor market is stable, but gradually loosening at the margins.

Directional signal: ➖⚠️

📉 VIX (Market Fear) — Big Spike (Risk-Off Mood)

The VIX jumped to 20.82 (back above the “20” stress line), signaling a meaningful uptick in market anxiety and uncertainty. Even if the “why” is tech/AI-driven this week, the signal is broader: investors are paying up for protection.

Directional signal: 📉

📈 CPI / Inflation — Cooling (Real Relief)

January CPI came in cooler: +0.2% MoM and 2.4% YoY (down from ~2.7% in December). That’s a tangible “pressure release valve” for consumer mood.

Directional signal: 📈

📉 Gas Prices — Small Uptick

National average ~$2.90, slightly higher than last week (~$2.87–$2.88). Not a major hit, but it’s the wrong direction heading into a travel weekend.

Directional signal: 📉 (mild)

📈 Mortgage Rates — Slight Improvement

30-year fixed 6.09% (down from 6.11%). Not a game-changer, but it’s steady progress and helps sentiment at the margin.

Directional signal: 📈

📉 AI / Tech Layoffs — Still a Background Anxiety

Even without a single headline-dominating layoff this week, the theme persists: AI efficiency + restructuring keeps “future job security” anxiety elevated, especially for white-collar voters.

Directional signal: 📉

🔥 15 Minutes a Week with ZPI = More Political Insight Than Most Insiders.

Zoose® is a multi-patented AI company founded by veteran campaign operative Patrick Allocco, creator of the Zoose Political Index (ZPI), a nonpartisan weekly model of U.S. elections and voter sentiment. Allocco appears regularly on Newsmax to break down the data for a national audience.